Physics recognizes four fundamental forces. However, throughout much of the twentieth century it was widely believed that one of them—the electric force—plays no macroscopic role in the Universe. For example, while positively charged atoms exist, positively charged stars were considered impossible.

This conviction was not the result of countless symposia devoted to a “non‑electric Universe.” Rather, it arose from a simple idea: the electric force is too strong to act on macroscopic scales. For two free protons in a vacuum, electrostatic repulsion is approximately 1036 times stronger than gravitational attraction. Although matter throughout the Universe consists of enormous positive and negative charges, the extreme strength of the electric force seemed to prevent any large‑scale separation of charge. Consequently, the theoretically infinite range of the electric force appeared as superfluous as the fifth leg of an antelope.

Any deviation from this allegedly neutral Universe should therefore have been easy to observe. An excess of only 0.003 grams of free protons would be sufficient to disrupt the Sun, since their electrostatic repulsion would exceed the Sun’s gravitational attraction by about 50%, despite its enormous mass of 2·1033 grams. Even an imbalance of 1 microgram of protons would not destroy the Sun, but if distributed unevenly it should deform it significantly. The strength of the electric force lies far beyond our everyday intuition: even microscopic charges should produce macroscopic effects.

Observations show that macroscopic electric effects may have cosmological consequences, such as galaxies that do not follow simple gravitational dynamics or the accelerated expansion of the Universe—phenomena often attributed to dark matter or dark energy. It is also well known that the Sun emits not merely micrograms but billions of tons of charged matter, which caused major power outages in Canada and Sweden in March 1989. Clearly, something is inconsistent with the traditional assumption of a purely neutral Universe.

Not only the magnitude but also the direction of the electric force should reveal its presence if charges are not fully neutralized. Gravity can only attract, whereas the electric force can both attract and repel. A simple method of detecting large‑scale charge separation is therefore to search for repulsive effects. An excess of one microgram of free protons should at least produce electrostatic solar geysers. Although none were reported between the time of Galileo and Hale, such structures were in fact observed by G. E. Hale in 1892 using his spectroheliograph.

These prominences were not hot, spherical clouds but filamentary structures, indicative of an electric origin through their pinch effect and ionized nature. Hale regarded this as evidence that electric charges on the Sun generate the magnetic fields of sunspots. In 1941, R. S. Richardson re‑examined Hale’s interpretation, but the assumption of a constant solar charge led to contradictions.

The solar dynamo was subsequently introduced to resolve these issues. Yet the dynamo itself remained elusive: its location, voltage, current, power, dimensions, and electric circuit could not be demonstrated. The SOHO mission was designed in part to detect it, but neither the dynamo nor its proposed products—deep, extended magnetic flux tubes—were observed. Likewise, the heating of the corona and the origin of the solar wind remain open problems.

Numerous astronomers—including Bahcall, Haxton, Hoeksema, Lang, Longair, and Phillips—have documented these and many other inconsistencies without offering a definitive solution. My book The Electric Universe proposes such a solution without invoking new measurements or speculative particles such as WIMPs. Only two long‑established facts must be considered:

- The electron has a mass 1836 times smaller than that of the proton.

- In a plasma, photons propagate along extremely long zigzag paths.

As a consequence, electrons move about 43 times faster than protons at the same temperature, allowing many more electrons than protons to escape from the solar core. The core therefore becomes continuously positively charged. In essence, fusion energy separates electric charges through the temperature gradient it produces.

Why does the Sun not explode electrostatically as soon as this charge imbalance appears? As long as the solar core remains a plasma, photons—whether transporting heat or electrostatic interaction—travel along paths whose total length amounts to many light‑years. This makes both heat transfer and electrostatic interaction inefficient. Plasma obeys the gas laws, yet it is not a gas: it is opaque to both thermal radiation and electric forces, which are carried by the same photons.

An electrostatic explosion would occur only later, when the positively charged core cools below roughly 7,000 K and recombination produces a neutral gas. Photons would then propagate along short, straight paths, suddenly transmitting strong electrostatic repulsion between ions. Such an event would manifest as a gamma‑ray burst. This provides an explanation for the absence of red white dwarfs in the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram: without such explosions, cold white dwarfs should vastly outnumber hot ones because of their slower cooling.

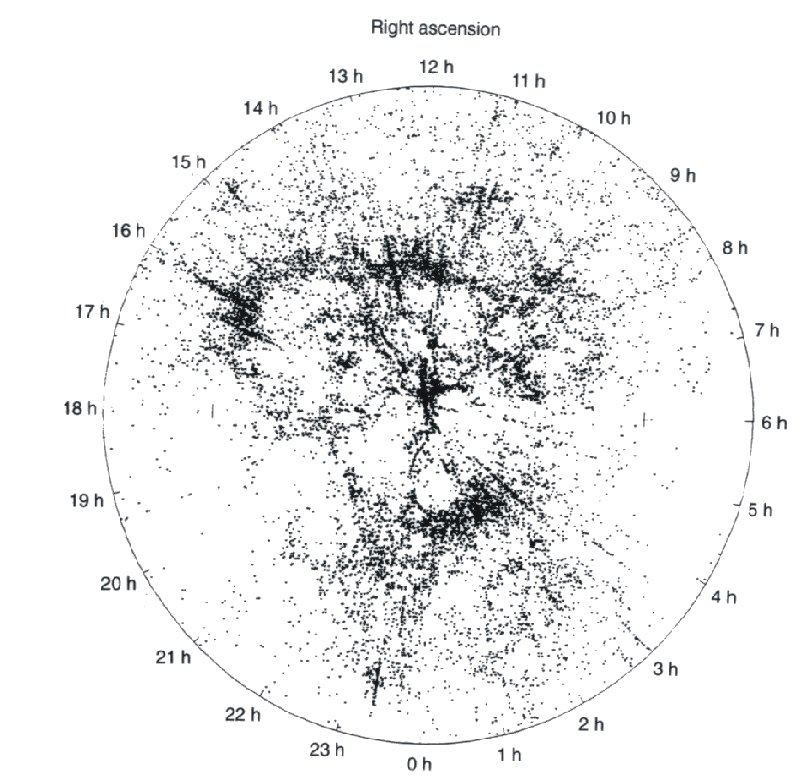

The Universe itself is dominated by filaments and vast voids. These filaments cannot be produced by nuclear forces and are poorly explained by gravity alone. An electric force of infinite range naturally accounts for sparks, lightning, spicules, solar filaments, coronal mass ejections, supernova remnants, stellar and galactic jets, and even supercluster filaments such as the Aquarius filament extending over a gigalight‑year. Electrostatic attraction and repulsion drive the motion of charged matter and produce the characteristic circular cross‑sections of filaments via the pinch effect.

Gravity forms spheres; electric forces form filaments—both with circular symmetry across vastly different scales. The infinite range of the electric force is therefore not superfluous: it shapes not only sparks, but the largest structures in the Universe.

This perspective remained hidden because classical teaching assumed that a thermoelement requires two wires. My own work showed that the two thermowires act as two generators. After establishing this law in 1978, it took another sixteen years to recognize that conducting stars behave similarly: hot regions become positively charged and cold regions negatively charged purely due to temperature differences, without bulk motion. Lenz’s law poses no obstacle, as it does not halt solar rotation through induced currents.

The Electric Universe is remarkable in its elegant simplicity. Nevertheless, the twentieth century will likely remain the century of astronomical mysteries, largely because the macroscopic effects of the electric force were overlooked.